The ketogenic diet is all over the media lately and I find myself having a conversation about it with a patient at least once per day. Where did this popular diet come from and what does it mean for people with diabetes?

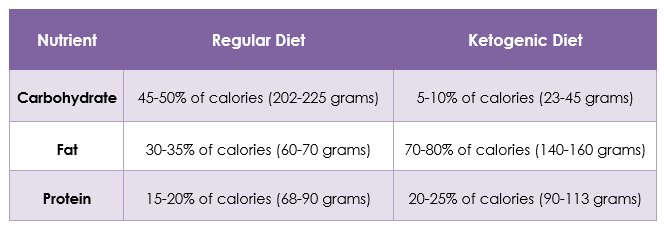

A ketogenic diet is very low in carbohydrate, very high in fat, and has moderate amounts of protein (see table below). Typically, the body turns carbohydrates into glucose, or sugar, which gets stored as energy in muscles and liver. When the body is deprived of carbohydrates and all of the stores have been used up, the body starts using fat for energy. This process creates byproducts called ketone bodies which can be used to feed the brain when there is not enough glucose available. When someone is producing significant levels of ketone bodies, they are said to be in ketosis and that’s how the ketogenic diet got its name.

The ketogenic diet was first developed in the 1920s to help children with epilepsy, a seizure disorder.(1) Researchers found that when the brain used ketone bodies for energy instead of glucose, children had fewer seizures. With the discovery of new medications for epilepsy, the ketogenic diet became less popular by the 1940s. However, following a news story in 1994 about a child whose epilepsy improved from a ketogenic diet, researchers began studying the diet again and not just for epilepsy. Since then, it has continued to grow in popularity.

People with diabetes might notice that the words ‘ketosis’ and ‘ketogenic’ sound very similar to a scary word, ‘ketoacidosis’. Ketoacidosis is a deadly condition where the body doesn’t have enough insulin to process glucose. In this situation, the body produces very high levels of ketone bodies so quickly that the blood becomes acidic. A ketogenic diet is not likely to increase ketone bodies to a high enough level to cause ketoacidosis; however, people with diabetes should always speak with their health care providers before starting a new diet.

Ketogenic diets have been studied in people with diabetes. Based on this research, the American Diabetes Association acknowledges these diets in the 2018 Standards of Care. “While some studies have shown modest benefits of very low–carbohydrate or ketogenic diets (less than 50-g carbohydrate per day), this approach may only be appropriate for short-term implementation (up to 3–4 months) if desired by the patient, as there is little long-term research citing benefits or harm.”(2)

That brings up a big challenge with the ketogenic diet: we don’t have long-term research so we don’t know if this is a diet that somebody can safely follow for the rest of their life. In the short-term, it might be helpful for someone trying to improve their A1C or lose weight, but in the long-term, there could be negative effects. Some known risks of a ketogenic diet include dehydration, gout, kidney stones, osteoporosis, and nutrient deficiencies. (3) For this reason, it’s important to work closely with a Registered Dietitian if you decide to test out a ketogenic diet. They can help you to weigh the risks and benefits of a ketogenic diet and support you in following one successfully.

Table: Comparison of a regular diet to a ketogenic diet for a person eating 1800 calories daily.

References

- Wheless, James. History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Supplement 8):3–5

- American Diabetes Association. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41(Supplement 1): S38-S50.

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Diet Review: Ketogenic Diet for Weight Loss . June 2018. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-weight/diet-reviews/ketogenic-diet/